USS Wyoming (BB-32) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

USS ''Wyoming'' (BB-32) was the

''Wyoming'' then took part in gunnery drills off the

''Wyoming'' then took part in gunnery drills off the

''Wyoming'' operated out of the Chesapeake Bay area for the next seven months, training engine-room personnel for the expanding American fleet. On 25 November, Battleship Division 9 (BatDiv 9), which at that time comprised ''Wyoming'', , , and , departed the US, bound for Britain. BatDiv 9 was to reinforce the British

''Wyoming'' operated out of the Chesapeake Bay area for the next seven months, training engine-room personnel for the expanding American fleet. On 25 November, Battleship Division 9 (BatDiv 9), which at that time comprised ''Wyoming'', , , and , departed the US, bound for Britain. BatDiv 9 was to reinforce the British

On 1 February, ''Wyoming'' steamed out of New York to join the annual fleet maneuvers off Cuba, before returning to New York on 14 April. On 12 May, she left port to help guide a group of Navy

On 1 February, ''Wyoming'' steamed out of New York to join the annual fleet maneuvers off Cuba, before returning to New York on 14 April. On 12 May, she left port to help guide a group of Navy

On 14 February 1925, ''Wyoming'' again passed through the Panama Canal to return to the Pacific. There, she joined fleet exercises off California. She then proceeded to Hawaii, where she remained from late April to early June. She visited San Diego on 18–22 June, and then returned to the east coast via the Panama Canal, arriving in New York on 17 July. A cruise to Cuba and Haiti followed, after which ''Wyoming'' returned to the New York Navy Yard for an overhaul that lasted from 23 November to 26 January 1926. During this period, then-

On 14 February 1925, ''Wyoming'' again passed through the Panama Canal to return to the Pacific. There, she joined fleet exercises off California. She then proceeded to Hawaii, where she remained from late April to early June. She visited San Diego on 18–22 June, and then returned to the east coast via the Panama Canal, arriving in New York on 17 July. A cruise to Cuba and Haiti followed, after which ''Wyoming'' returned to the New York Navy Yard for an overhaul that lasted from 23 November to 26 January 1926. During this period, then-

After returning to Philadelphia on 1 January 1931, ''Wyoming'' was placed on reduced commission. Under the terms of the

After returning to Philadelphia on 1 January 1931, ''Wyoming'' was placed on reduced commission. Under the terms of the

Following the United States' entrance into World War II, ''Wyoming'' performed her normal duties as a gunnery training ship with the Operational Training Command, United States Atlantic Fleet starting in February 1942. She operated primarily in the Chesapeake Bay area, and frequent sightings of the ship steaming around the bay earned her the nickname "Chesapeake Raider". ''Wyoming'' was very busy, training thousands of anti-aircraft gunners on weapons ranging from light .50 caliber (12.7 mm) guns to medium-caliber 5-inch guns for the rapidly expanding American fleet. Early in the war, the Navy briefly considered converting ''Wyoming'' back to her battleship configuration, but decided against the plan.

These duties continued throughout the rest of the war. ''Wyoming'' was modernized at Norfolk Navy Yard from 12 January to 3 April 1944; the reconstruction removed the last of her three 12-inch gun turrets, and replaced them with four twin and two single enclosed mounts for 5-inch/38 caliber guns. New fire control radars were also installed; these modifications allowed ''Wyoming'' to train anti-aircraft gunners with the most modern equipment they would use while in combat with the fleet. She was back in service in the Chesapeake Bay by 10 April. Over the course of the war, ''Wyoming'' trained an estimated 35,000 gunners on seven different types of guns: 5-inch, 3-inch, 1.1-inch, 40-millimeter, 20-millimeter, .50 caliber, and .30 caliber (7.62 mm) weapons. Due to her extensive use as a gunnery training ship, she claimed the distinction of firing more ammunition than any other ship in the fleet during the war.

''Wyoming'' finished her gunnery training duties in the Chesapeake area on 30 June 1945, when she left Norfolk for the New York Navy Yard, for further modifications. Work was completed by 13 July, after which she left for

Following the United States' entrance into World War II, ''Wyoming'' performed her normal duties as a gunnery training ship with the Operational Training Command, United States Atlantic Fleet starting in February 1942. She operated primarily in the Chesapeake Bay area, and frequent sightings of the ship steaming around the bay earned her the nickname "Chesapeake Raider". ''Wyoming'' was very busy, training thousands of anti-aircraft gunners on weapons ranging from light .50 caliber (12.7 mm) guns to medium-caliber 5-inch guns for the rapidly expanding American fleet. Early in the war, the Navy briefly considered converting ''Wyoming'' back to her battleship configuration, but decided against the plan.

These duties continued throughout the rest of the war. ''Wyoming'' was modernized at Norfolk Navy Yard from 12 January to 3 April 1944; the reconstruction removed the last of her three 12-inch gun turrets, and replaced them with four twin and two single enclosed mounts for 5-inch/38 caliber guns. New fire control radars were also installed; these modifications allowed ''Wyoming'' to train anti-aircraft gunners with the most modern equipment they would use while in combat with the fleet. She was back in service in the Chesapeake Bay by 10 April. Over the course of the war, ''Wyoming'' trained an estimated 35,000 gunners on seven different types of guns: 5-inch, 3-inch, 1.1-inch, 40-millimeter, 20-millimeter, .50 caliber, and .30 caliber (7.62 mm) weapons. Due to her extensive use as a gunnery training ship, she claimed the distinction of firing more ammunition than any other ship in the fleet during the war.

''Wyoming'' finished her gunnery training duties in the Chesapeake area on 30 June 1945, when she left Norfolk for the New York Navy Yard, for further modifications. Work was completed by 13 July, after which she left for

NavSource Naval History, USS Wyoming (BB-32)

Log of the U.S. Ship ''Wyoming'', 1936, MS 89

an

U.S.S. ''Wyoming Diary'', 1917-1919 (bulk 1918), MS 31

held by Special Collections & Archives, Nimitz Library at the United States Naval Academy {{DEFAULTSORT:Wyoming (BB-32) Wyoming-class battleships Ships built by William Cramp & Sons 1911 ships World War I battleships of the United States World War II battleships of the United States

lead ship

The lead ship, name ship, or class leader is the first of a series or class of ships all constructed according to the same general design. The term is applicable to naval ships and large civilian vessels.

Large ships are very complex and may ...

of her class of dreadnought

The dreadnought (alternatively spelled dreadnaught) was the predominant type of battleship in the early 20th century. The first of the kind, the Royal Navy's , had such an impact when launched in 1906 that similar battleships built after her ...

battleship

A battleship is a large armored warship with a main battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1880s to describe a type of ...

s and was the third ship of the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

named Wyoming, although she was only the second named in honor of the 44th state. ''Wyoming'' was laid down at the William Cramp & Sons

William Cramp & Sons Shipbuilding Company (also known as William Cramp & Sons Ship & Engine Building Company) of Philadelphia was founded in 1830 by William Cramp, and was the preeminent U.S. iron shipbuilder of the late 19th century.

Company hi ...

in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

in February 1910, was launched in May 1911, and was completed in September 1912. She was armed with a main battery

A main battery is the primary weapon or group of weapons around which a warship is designed. As such, a main battery was historically a gun or group of guns, as in the broadsides of cannon on a ship of the line. Later, this came to be turreted ...

of twelve guns and capable of a top speed of .

During the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, she was part of the Battleship Division Nine, which was attached to the British Grand Fleet

The Grand Fleet was the main battlefleet of the Royal Navy during the First World War. It was established in August 1914 and disbanded in April 1919. Its main base was Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands.

History

Formed in August 1914 from the ...

as the 6th Battle Squadron

The 6th Battle Squadron was a squadron of the British Royal Navy consisting of Battleships serving in the Grand Fleet and existed from 1913 to 1917.

History First World War August 1914

In August 1914, the 6th Battle Squadron was based at Portl ...

. During the war, she was primarily tasked with patrolling in the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian S ...

and escorting convoys to Norway. She served in both the Atlantic and Pacific Fleets throughout the 1920s, and in 1931–1932, she was converted into a training ship

A training ship is a ship used to train students as sailors. The term is mostly used to describe ships employed by navies to train future officers. Essentially there are two types: those used for training at sea and old hulks used to house classr ...

according to the terms of the London Naval Treaty

The London Naval Treaty, officially the Treaty for the Limitation and Reduction of Naval Armament, was an agreement between the United Kingdom, Japan, France, Italy, and the United States that was signed on 22 April 1930. Seeking to address is ...

of 1930.

''Wyoming'' served as a training ship throughout the 1930s, and in November 1941, she became a gunnery ship. She operated primarily in the Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The Bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula (including the parts: the ...

area, which earned her the nickname "Chesapeake Raider". In this capacity, she trained some 35,000 gunners for the hugely expanded US Navy during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. She continued in this duty until 1947, when she was decommissioned on 1 August and subsequently sold for scrap; she was broken up in New York starting in December 1947.

Design

''Wyoming'' waslong overall

__NOTOC__

Length overall (LOA, o/a, o.a. or oa) is the maximum length of a vessel's hull measured parallel to the waterline. This length is important while docking the ship. It is the most commonly used way of expressing the size of a ship, an ...

and had a beam

Beam may refer to:

Streams of particles or energy

*Light beam, or beam of light, a directional projection of light energy

**Laser beam

*Particle beam, a stream of charged or neutral particles

**Charged particle beam, a spatially localized grou ...

of and a draft

Draft, The Draft, or Draught may refer to:

Watercraft dimensions

* Draft (hull), the distance from waterline to keel of a vessel

* Draft (sail), degree of curvature in a sail

* Air draft, distance from waterline to the highest point on a vessel ...

of . She displaced as designed and up to at full load

The displacement or displacement tonnage of a ship is its weight. As the term indicates, it is measured indirectly, using Archimedes' principle, by first calculating the volume of water displaced by the ship, then converting that value into wei ...

. The ship was powered by four-shaft Parsons

Parsons may refer to:

Places

In the United States:

* Parsons, Kansas, a city

* Parsons, Missouri, an unincorporated community

* Parsons, Tennessee, a city

* Parsons, West Virginia, a town

* Camp Parsons, a Boy Scout camp in the state of Washingt ...

steam turbines

A steam turbine is a machine that extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam and uses it to do mechanical work on a rotating output shaft. Its modern manifestation was invented by Charles Parsons in 1884. Fabrication of a modern steam turbin ...

and twelve coal-fired Babcock & Wilcox

Babcock & Wilcox is an American renewable, environmental and thermal energy technologies and service provider that is active and has operations in many international markets across the globe with its headquarters in Akron, Ohio, USA. Historicall ...

boiler

A boiler is a closed vessel in which fluid (generally water) is heated. The fluid does not necessarily boil. The heated or vaporized fluid exits the boiler for use in various processes or heating applications, including water heating, central h ...

s rated at , generating a top speed of . The ship had a cruising range of at a speed of .

The ship was armed with a main battery

A main battery is the primary weapon or group of weapons around which a warship is designed. As such, a main battery was historically a gun or group of guns, as in the broadsides of cannon on a ship of the line. Later, this came to be turreted ...

of twelve 12-inch/50 caliber Mark 7 guns in six Mark 9 twin gun turret

A gun turret (or simply turret) is a mounting platform from which weapons can be fired that affords protection, visibility and ability to turn and aim. A modern gun turret is generally a rotatable weapon mount that houses the crew or mechani ...

s on the centerline, two of which were placed in a superfiring pair forward. The other four turrets were placed aft of the superstructure

A superstructure is an upward extension of an existing structure above a baseline. This term is applied to various kinds of physical structures such as buildings, bridges, or ships.

Aboard ships and large boats

On water craft, the superstruct ...

in two superfiring pairs. The secondary battery consisted of twenty-one /51 caliber guns mounted in casemate

A casemate is a fortified gun emplacement or armored structure from which artillery, guns are fired, in a fortification, warship, or armoured fighting vehicle.Webster's New Collegiate Dictionary

When referring to Ancient history, antiquity, th ...

s along the side of the hull. The main armored belt

Belt armor is a layer of heavy metal vehicle armor, armor plated onto or within the outer hulls of warships, typically on battleships, battlecruisers and cruisers, and aircraft carriers.

The belt armor is designed to prevent projectiles from p ...

was thick, while the gun turrets had thick faces. The conning tower

A conning tower is a raised platform on a ship or submarine, often armored, from which an officer in charge can conn the vessel, controlling movements of the ship by giving orders to those responsible for the ship's engine, rudder, lines, and gro ...

had thick sides.

Modifications

In 1925, ''Wyoming'' was modernized in the Philadelphia Navy Yard. Her displacement increased significantly, to standard and full load. Her beam was widened to , primarily from the installation ofanti-torpedo bulge

The anti-torpedo bulge (also known as an anti-torpedo blister) is a form of defence against naval torpedoes occasionally employed in warship construction in the period between the First and Second World Wars. It involved fitting (or retrofittin ...

s, and draft increased to . Her twelve coal-fired boilers were replaced with four White-Forster oil-fired boilers that had been intended for the ships cancelled under the terms of the Washington Naval Treaty

The Washington Naval Treaty, also known as the Five-Power Treaty, was a treaty signed during 1922 among the major Allies of World War I, which agreed to prevent an arms race by limiting naval construction. It was negotiated at the Washington Nav ...

; performance remained the same as the older boilers. The ship's deck armor was strengthened by the addition of of armor to the second deck between the end barbettes, plus of armor on the third deck on the bow and stern. The deck armor over the engines and boilers was increased by and , respectively. Five of the 5-inch guns were removed and eight /50 caliber anti-aircraft

Anti-aircraft warfare, counter-air or air defence forces is the battlespace response to aerial warfare, defined by NATO as "all measures designed to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of hostile air action".AAP-6 It includes surface based, ...

guns were installed. The mainmast was removed to provide space for an aircraft catapult mounted on the Number 3 turret amidships

This glossary of nautical terms is an alphabetical listing of terms and expressions connected with ships, shipping, seamanship and navigation on water (mostly though not necessarily on the sea). Some remain current, while many date from the 17th t ...

.

Service history

''Wyoming'' was laid down at theWilliam Cramp & Sons

William Cramp & Sons Shipbuilding Company (also known as William Cramp & Sons Ship & Engine Building Company) of Philadelphia was founded in 1830 by William Cramp, and was the preeminent U.S. iron shipbuilder of the late 19th century.

Company hi ...

shipyard in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

on 9 February 1910, and was launched on 25 May 1911. She was completed a year and four months later, on 25 September 1912. After her commissioning, the final fitting-out

Fitting out, or outfitting, is the process in shipbuilding that follows the float-out/launching of a vessel and precedes sea trials. It is the period when all the remaining construction of the ship is completed and readied for delivery to her o ...

work was completed at the New York Navy Yard

The Brooklyn Navy Yard (originally known as the New York Navy Yard) is a shipyard and industrial complex located in northwest Brooklyn in New York City, New York (state), New York. The Navy Yard is located on the East River in Wallabout Bay, a ...

over the next three months. She then proceeded to join the rest of the fleet at Hampton Roads

Hampton Roads is the name of both a body of water in the United States that serves as a wide channel for the James River, James, Nansemond River, Nansemond and Elizabeth River (Virginia), Elizabeth rivers between Old Point Comfort and Sewell's ...

on 30 December, where she became the flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the fi ...

of Rear Admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star "admiral" rank. It is often regarde ...

Charles J. Badger, the commander of the Atlantic Fleet. ''Wyoming'' left Hampton Roads on 6 January 1913, bound for the Caribbean. She visited the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal ( es, Canal de Panamá, link=no) is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean and divides North and South America. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a conduit ...

, which was nearing completion, and then participated in fleet exercises off Cuba. The ship was back in port in Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The Bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula (including the parts: the ...

on 4 March.

''Wyoming'' then took part in gunnery drills off the

''Wyoming'' then took part in gunnery drills off the Virginia Capes

The Virginia Capes are the two capes, Cape Charles to the north and Cape Henry to the south, that define the entrance to Chesapeake Bay on the eastern coast of North America.

In 1610, a supply ship learned of the famine at Jamestown when it l ...

, and on 18 April, entered drydock at the New York Navy Yard for some repairs, which lasted until 7 May. She joined the rest of the fleet for maneuvers off Block Island

Block Island is an island in the U.S. state of Rhode Island located in Block Island Sound approximately south of the mainland and east of Montauk Point, Long Island, New York, named after Dutch explorer Adriaen Block. It is part of Washingt ...

that lasted from 7–24 May. During the maneuvers, the ship's machinery proved troublesome, which necessitated repairs at Newport from 9–19 May. At the end of the month, she was in New York harbor, to participate in the ceremonies for the dedication of the monument to the armored cruiser

The armored cruiser was a type of warship of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was designed like other types of cruisers to operate as a long-range, independent warship, capable of defeating any ship apart from a battleship and fast eno ...

, which had been destroyed in Havana

Havana (; Spanish: ''La Habana'' ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of the La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.

harbor on 15 February 1898. On 4 June, ''Wyoming'' steamed to Annapolis

Annapolis ( ) is the capital city of the U.S. state of Maryland and the county seat of, and only incorporated city in, Anne Arundel County. Situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east o ...

, where she took on a crew of naval cadets from the Naval Academy

A naval academy provides education for prospective naval officers.

See also

* Military academy

A military academy or service academy is an educational institution which prepares candidates for service in the officer corps. It normally pro ...

for a summer midshipman cruise.

After returning the midshipmen to Annapolis on 24–25 August, ''Wyoming'' took part in gunnery and torpedo training over the next few weeks. On 16 September, she returned to New York for repairs, which lasted until 2 October. She then ran full–power sea trial

A sea trial is the testing phase of a watercraft (including boats, ships, and submarines). It is also referred to as a " shakedown cruise" by many naval personnel. It is usually the last phase of construction and takes place on open water, and ...

s before proceeding to the Virginia Capes, where she participated in another round of fleet maneuvers. Next, she departed for a European goodwill cruise on 26 October. She toured the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ea ...

, stopping in Valletta, Malta

Valletta (, mt, il-Belt Valletta, ) is an administrative unit and capital of Malta. Located on the main island, between Marsamxett Harbour to the west and the Grand Harbour to the east, its population within administrative limits in 2014 wa ...

, Naples, Italy

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

, and Villefranche, France. She departed France on 30 November, and arrived in New York on 15 December. There, she went into dock at the New York Navy Yard for periodic repairs, which lasted until January 1914. On the 6th, ''Wyoming'' left for Hampton Roads, where she took on coal in preparation for the annual fleet maneuvers in the Caribbean.

The exercises lasted from 26 January to 15 March, and the fleet was based in Guantanamo Bay Naval Base

Guantanamo Bay Naval Base ( es, Base Naval de la Bahía de Guantánamo), officially known as Naval Station Guantanamo Bay or NSGB, (also called GTMO, pronounced Gitmo as jargon by members of the U.S. military) is a United States military base ...

in Cuba. ''Wyoming'' and the rest of the fleet then proceeded to Tangier Sound

Tangier Sound is a sound of the Chesapeake Bay bounded on the west by Tangier Island in Virginia, and Smith Island and South Marsh Island in Maryland, by Deal Island in Maryland on the north, and the mainland of the Eastern Shore of Maryland and ...

for additional training, including gunnery drills. On 3 April, ''Wyoming'' left the fleet for an overhaul in New York, which lasted until 9 May. She then returned to Hampton Roads, where she took on a contingent of troops and ferried them to Veracruz

Veracruz (), formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave), is one of the 31 states which, along with Me ...

, arriving on 18 May. The US had intervened in the Mexican Revolution

The Mexican Revolution ( es, Revolución Mexicana) was an extended sequence of armed regional conflicts in Mexico from approximately 1910 to 1920. It has been called "the defining event of modern Mexican history". It resulted in the destruction ...

and occupied Veracruz to safeguard American citizens there. ''Wyoming'' cruised off Veracruz into the Autumn of 1914, at which point she returned to the Virginia Capes for exercises. On 6 October, she entered New York for repairs; this work lasted until 17 January 1915.

''Wyoming'' then proceeded to Hampton Roads, and then to Cuba, where she joined the fleet for the annual maneuvers off Cuba. These lasted until April, when she returned to the US. She participated in more exercises off Block Island over the next several months, and on 20 December, she returned to New York for another overhaul. On 6 January 1916, she emerged from dry dock, and then proceeded to the Caribbean. On 16 January, she reached Culebra, Puerto Rico

Isla Culebra (, ''Snake Island'') is an island, town and municipality of Puerto Rico and geographically part of the Spanish Virgin Islands. It is located approximately east of the Puerto Rican mainland, west of St. Thomas and north of Vieque ...

, then visited Port-au-Prince

Port-au-Prince ( , ; ht, Pòtoprens ) is the capital and most populous city of Haiti. The city's population was estimated at 987,311 in 2015 with the metropolitan area estimated at a population of 2,618,894. The metropolitan area is define ...

, Haiti on 27 January. She entered port at Guantanamo the next day, and took part in fleet maneuvers until 10 April, after which she returned to New York. Another round of dockyard work took place from 16 April to 26 June. After returning to service, ''Wyoming'' took part in more maneuvers off the Virginia Capes for the remainder of the year. She left New York on 9 January 1917, bound for Cuban waters for exercises that lasted through mid-March. She left Cuba on 27 March, and was cruising off Yorktown, Virginia

Yorktown is a census-designated place (CDP) in York County, Virginia. It is the county seat of York County, one of the eight original shires formed in colonial Virginia in 1682. Yorktown's population was 195 as of the 2010 census, while York Cou ...

when the US declared war on Germany on 6 April, formally entering World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

.

World War I

''Wyoming'' operated out of the Chesapeake Bay area for the next seven months, training engine-room personnel for the expanding American fleet. On 25 November, Battleship Division 9 (BatDiv 9), which at that time comprised ''Wyoming'', , , and , departed the US, bound for Britain. BatDiv 9 was to reinforce the British

''Wyoming'' operated out of the Chesapeake Bay area for the next seven months, training engine-room personnel for the expanding American fleet. On 25 November, Battleship Division 9 (BatDiv 9), which at that time comprised ''Wyoming'', , , and , departed the US, bound for Britain. BatDiv 9 was to reinforce the British Grand Fleet

The Grand Fleet was the main battlefleet of the Royal Navy during the First World War. It was established in August 1914 and disbanded in April 1919. Its main base was Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands.

History

Formed in August 1914 from the ...

at its base in Scapa Flow

Scapa Flow viewed from its eastern end in June 2009

Scapa Flow (; ) is a body of water in the Orkney Islands, Scotland, sheltered by the islands of Mainland, Graemsay, Burray,S. C. George, ''Jutland to Junkyard'', 1973. South Ronaldsay and ...

. The American ships reached Scapa on 7 December, where they became the 6th Battle Squadron

The 6th Battle Squadron was a squadron of the British Royal Navy consisting of Battleships serving in the Grand Fleet and existed from 1913 to 1917.

History First World War August 1914

In August 1914, the 6th Battle Squadron was based at Portl ...

of the Grand Fleet. The American ships drilled with their British counterparts from December 1917 to February 1918.

On 6 February, ''Wyoming'' and the other American battleships undertook their first wartime operation, to escort a convoy to Stavanger

Stavanger (, , American English, US usually , ) is a city and municipalities of Norway, municipality in Norway. It is the fourth largest city and third largest metropolitan area in Norway (through conurbation with neighboring Sandnes) and the a ...

, Norway, in company with eight British destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed in ...

s. On 7 February, lookouts on several ships, including ''Wyoming'', thought they spotted German U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare role ...

s attacking the ships with torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, and with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, su ...

es, though these proved to be incorrect reports. The convoy successfully reached Norway two days later; the return trip to Scapa Flow took another two days. ''Wyoming'' patrolled in the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian S ...

for the next several months, watching for a sortie by the German High Seas Fleet

The High Seas Fleet (''Hochseeflotte'') was the battle fleet of the German Imperial Navy and saw action during the First World War. The formation was created in February 1907, when the Home Fleet (''Heimatflotte'') was renamed as the High Seas ...

. On 30 June, ''Wyoming'' and the rest of the 6th Battle Squadron covered a minelaying operation in the North Sea; the operation lasted until 2 July. During the operation, jumpy crewmen again incorrectly reported U-boat sightings, and ''Wyoming'' opened fire on the supposed targets. On the return voyage, the 6th Battle Squadron joined up with Convoy HZ40, which was returning from Norway.

On 14 October, ''New York'' collided with a U-boat and sank it. The collision nevertheless damaged her screws, which forced Rodman to transfer his flag from ''New York'' to ''Wyoming'' while the former was in dock for repair. On 21 November, after the Armistice with Germany

The Armistice of 11 November 1918 was the armistice signed at Le Francport near Compiègne that ended fighting on land, sea, and air in World War I between the Entente and their last remaining opponent, Germany. Previous armistices ...

ended the war, ''Wyoming'' and an Allied fleet of some 370 warships met the High Seas Fleet in the North Sea and escorted it into internment in Scapa Flow. On 12 December, ''Wyoming'', now the flagship of Rear Admiral William Sims

William Sowden Sims (October 15, 1858 – September 28, 1936) was an admiral in the United States Navy who fought during the late 19th and early 20th centuries to modernize the navy. During World War I, he commanded all United States naval force ...

, the new BatDiv 9 commander, left Britain for France. There, she rendezvoused off Brest, France

Brest (; ) is a port city in the Finistère department, Brittany. Located in a sheltered bay not far from the western tip of the peninsula, and the western extremity of metropolitan France, Brest is an important harbour and the second French mi ...

, with , which was carrying President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

to the peace negotiations in Paris. ''Wyoming'' then returned to Britain two days later before departing for the US, arriving in New York on 25 December. She remained there through the new year, and on 18 January 1919, she became the flagship of BatDiv 7, flying the flag of Rear Admiral Robert Coontz

Robert Edward Coontz (June 11, 1864 – January 26, 1935) was an admiral in the United States Navy, who sailed with the Great White Fleet and served as the second Chief of Naval Operations.

Early life

Robert Coontz, son of Benton Coontz, w ...

.

Inter-war period

1919–1924

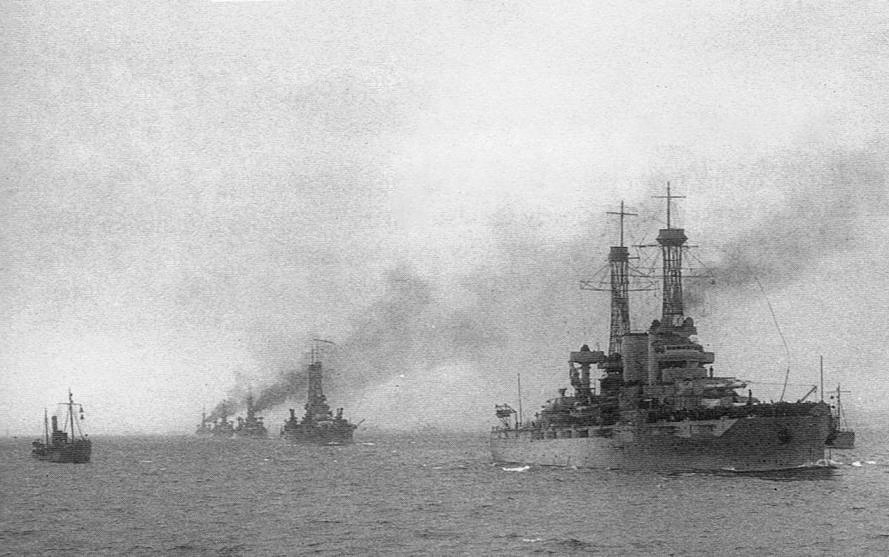

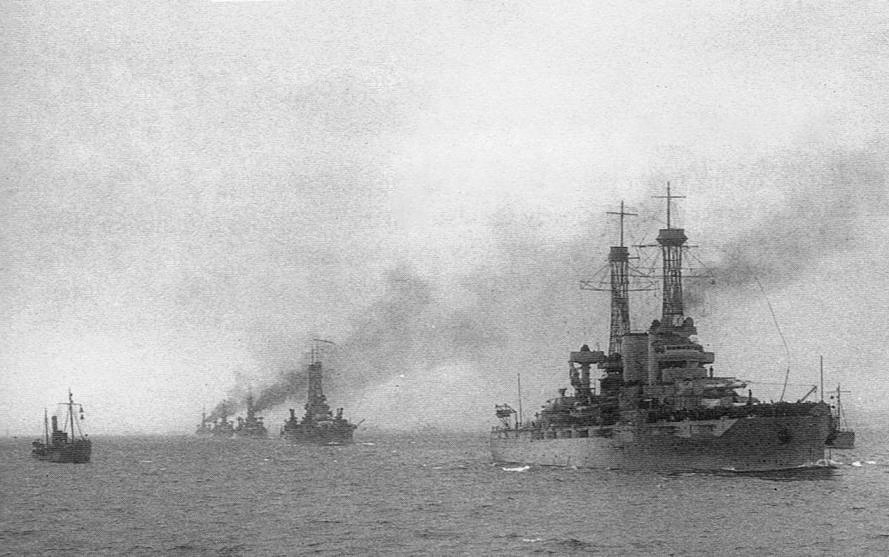

On 1 February, ''Wyoming'' steamed out of New York to join the annual fleet maneuvers off Cuba, before returning to New York on 14 April. On 12 May, she left port to help guide a group of Navy

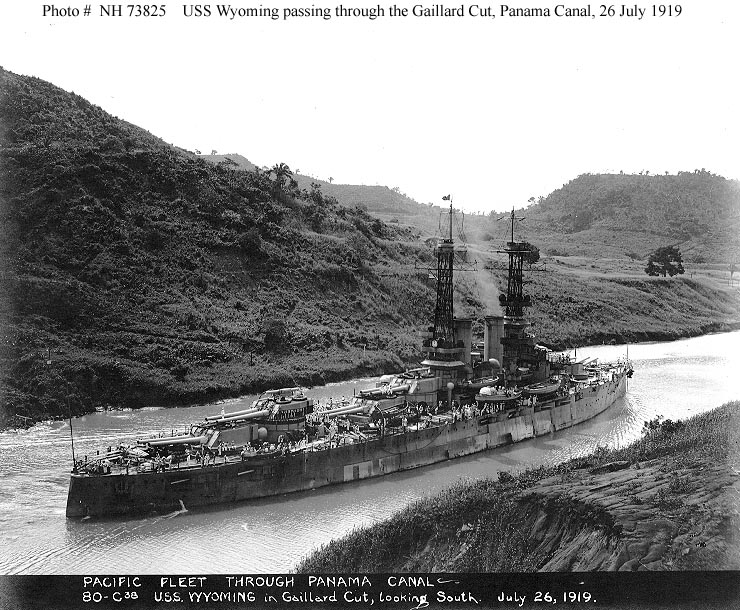

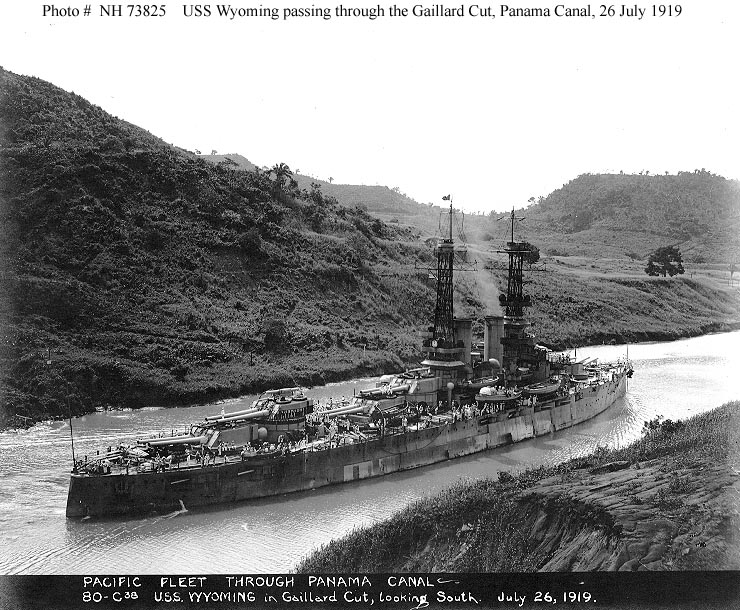

On 1 February, ''Wyoming'' steamed out of New York to join the annual fleet maneuvers off Cuba, before returning to New York on 14 April. On 12 May, she left port to help guide a group of Navy Curtiss NC

The Curtiss NC (Curtiss Navy Curtiss, nicknamed "Nancy boat" or "Nancy") was a flying boat built by Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company and used by the United States Navy from 1918 through the early 1920s. Ten of these aircraft were built, the mos ...

flying boat

A flying boat is a type of fixed-winged seaplane with a hull, allowing it to land on water. It differs from a floatplane in that a flying boat's fuselage is purpose-designed for floatation and contains a hull, while floatplanes rely on fusela ...

s as they made the first aerial transatlantic crossing. The battleship was back in port by 31 May. She then took on a crew of midshipmen for a training cruise off the Chesapeake Bay and Virginia Capes. After finishing the cruise, ''Wyoming'' entered dry dock at the Norfolk Navy Yard

The Norfolk Naval Shipyard, often called the Norfolk Navy Yard and abbreviated as NNSY, is a U.S. Navy facility in Portsmouth, Virginia, for building, remodeling and repairing the Navy's ships. It is the oldest and largest industrial facility tha ...

on 1 July for a modernization for service in the Pacific. Her secondary battery was reduced to sixteen 5-inch guns. After emerging from the shipyard, she became the flagship of BatDiv 6 of the newly designated Pacific Fleet. On 19 July, ''Wyoming'' and the rest of the Pacific Fleet departed the east coast, bound for the Pacific. The ships transited the Panama Canal later that month, and reached San Diego

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the List of United States cities by population, eigh ...

, California on 6 August.

On 9 August, ''Wyoming'' moved to San Pedro, where she was based for the next month. She went to the Puget Sound Navy Yard

Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, officially Puget Sound Naval Shipyard and Intermediate Maintenance Facility (PSNS & IMF), is a United States Navy shipyard covering 179 acres (0.7 km2) on Puget Sound at Bremerton, Washington in uninterrupted u ...

for an overhaul that lasted until 19 April 1920. On 4 May, she was back in San Pedro and resumed her normal routine of fleet maneuvers off the California coast. On 30 August, ''Wyoming'' left California for Hawaii, where she participated in more training exercises through September. She then returned to San Diego on 8 October for more maneuvers off the west coast. The ship left San Francisco on 5 January 1921 for a cruise to Central and South American waters; the trip culminated in Valparaíso

Valparaíso (; ) is a major city, seaport, naval base, and educational centre in the commune of Valparaíso, Chile. "Greater Valparaíso" is the second largest metropolitan area in the country. Valparaíso is located about northwest of Santiago ...

, Chile, where she was reviewed by the President of Chile

The president of Chile ( es, Presidente de Chile), officially known as the President of the Republic of Chile ( es, Presidente de la República de Chile), is the head of state and head of government of the Republic of Chile. The president is re ...

Arturo Alessandri Palma

Arturo Fortunato Alessandri Palma (; December 20, 1868 – August 24, 1950) was a Chilean political figure and reformer who served thrice as president of Chile, first from 1920 to 1924, then from March to October 1925, and finally from 1932 to ...

on 8 February. ''Wyoming'' then returned north, arriving in Puget Sound for repairs on 18 March.

On 2 August, ''Wyoming'' was in Balboa in the Canal Zone

The Panama Canal Zone ( es, Zona del Canal de Panamá), also simply known as the Canal Zone, was an unincorporated territory of the United States, located in the Isthmus of Panama, that existed from 1903 to 1979. It was located within the terri ...

, where she picked up Rear Admiral Rodman and a commission traveling from Peru back to New York. She arrived in New York on 19 August and rejoined the Atlantic Fleet. There, she became the flagship of Admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet, ...

Hilary P. Jones

Hilary Pollard Jones, Jr. (14 November 1863 – 1 January 1938) was an officer in the United States Navy during the Spanish–American War and World War I. During the early 1920s, he served as Commander in Chief, United States Fleet.

Early life ...

, the commander of the Atlantic Fleet. ''Wyoming'' spent the next three and a half years on the normal routine of winter fleet exercises off Cuba, followed by summer maneuvers off the east coast of the US. Throughout the period, she served as the flagship of Vice Admirals John McDonald, Newton McCully

Vice Admiral Newton Alexander McCully (1867–1951) was an officer in the United States Navy who served in the Spanish–American War and World War I.

Biography

McCully, the son of Newton A. and Caroline Fretwell McCully, was born on 19 June 186 ...

, and Josiah McKean in the Scouting Fleet. In the summer of 1924, she conducted a midshipman training cruise to Europe, and stopped in Torbay

Torbay is a borough and unitary authority in Devon, south west England. It is governed by Torbay Council and consists of of land, including the resort towns of Torquay, Paignton and Brixham, located on east-facing Tor Bay, part of Lyme ...

, Great Britain, Rotterdam

Rotterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Rotte'') is the second largest city and municipality in the Netherlands. It is in the province of South Holland, part of the North Sea mouth of the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta, via the ''"N ...

in the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

, Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

, and the Azores

)

, motto =( en, "Rather die free than subjected in peace")

, anthem= ( en, "Anthem of the Azores")

, image_map=Locator_map_of_Azores_in_EU.svg

, map_alt=Location of the Azores within the European Union

, map_caption=Location of the Azores wi ...

. In January and February 1924, the Navy conducted Fleet Problem II, III, and IV concurrently. During the FP III maneuvers, ''Wyoming'', her sister , and the two s stood in for the new s. During the FP IV portion of the maneuvers, ''Wyoming'' served in the "Blue" force, which represented the US Navy. She was attacked by "Black" aircraft, but the umpires judged ''Wyoming''s anti-aircraft fire and the escort fighters provided by to have effectively defended the fleet.

1925–1930

On 14 February 1925, ''Wyoming'' again passed through the Panama Canal to return to the Pacific. There, she joined fleet exercises off California. She then proceeded to Hawaii, where she remained from late April to early June. She visited San Diego on 18–22 June, and then returned to the east coast via the Panama Canal, arriving in New York on 17 July. A cruise to Cuba and Haiti followed, after which ''Wyoming'' returned to the New York Navy Yard for an overhaul that lasted from 23 November to 26 January 1926. During this period, then-

On 14 February 1925, ''Wyoming'' again passed through the Panama Canal to return to the Pacific. There, she joined fleet exercises off California. She then proceeded to Hawaii, where she remained from late April to early June. She visited San Diego on 18–22 June, and then returned to the east coast via the Panama Canal, arriving in New York on 17 July. A cruise to Cuba and Haiti followed, after which ''Wyoming'' returned to the New York Navy Yard for an overhaul that lasted from 23 November to 26 January 1926. During this period, then-Commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countries this naval rank is termed frigate captain.

...

William F. Halsey, Jr. came aboard as the ship's executive officer; he served on ''Wyoming'' until 4 January 1927.

''Wyoming'' then returned to the routine of winter maneuvers in the Caribbean and training cruises in the summer. In late August, the ship went to Philadelphia for an extensive modernization. Her old coal-fired boilers were replaced with new oil-fired models and anti-torpedo bulges were added to improve her resistance to underwater damage. The work was completed by 2 November, after which ''Wyoming'' conducted a shakedown cruise to Cuba and the Virgin Islands

The Virgin Islands ( es, Islas Vírgenes) are an archipelago in the Caribbean Sea. They are geologically and biogeographically the easternmost part of the Greater Antilles, the northern islands belonging to the Puerto Rico Trench and St. Croix ...

. She was back in Philadelphia on 7 December, and two days later, she returned to her post as the flagship of the Scouting Fleet, flying the flag of Vice Admiral Ashley Robertson.

''Wyoming'' spent the next three years in the Scouting Fleet. She conducted training cruises with Naval Reserve Officer Training Corps

The Naval Reserve Officers Training Corps (NROTC) program is a college-based, commissioned officer training program of the United States Navy and the United States Marine Corps.

Origins

A pilot Naval Reserve unit was established in September 19 ...

(NROTC) cadets from various universities, including Yale

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wor ...

, Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

, Georgia Tech

The Georgia Institute of Technology, commonly referred to as Georgia Tech or, in the state of Georgia, as Tech or The Institute, is a public research university and institute of technology in Atlanta, Georgia. Established in 1885, it is part of ...

, and Northwestern. These cruises went throughout the Atlantic, including to the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico ( es, Golfo de México) is an oceanic basin, ocean basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, largely surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of ...

, to the Azores, and to Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

. While on one of these cruises in November 1928, ''Wyoming'' picked up eight survivors from the wrecked steamship ; she took them to Norfolk on 16 November. On 19 September 1930, ''Wyoming'' was transferred from the Scouting Force to BatDiv 2, where she became the flagship of Rear Admiral Wat T. Cluverius

Wat Tyler Cluverius IV (December 4, 1934 – February 14, 2010) was an American diplomat with a focus on the Middle East.

Cluverius was born in Arlington, Massachusetts and grew up in Chicago, Illinois. Cluverius married the former Leah Konsta ...

. She served here until 4 November, when she was withdrawn from front-line service and became the flagship of the Training Squadron, flying the flag of Rear Admiral Harley H. Christy. Thereafter, she conducted a training cruise to the Gulf of Mexico.

1931–1941

After returning to Philadelphia on 1 January 1931, ''Wyoming'' was placed on reduced commission. Under the terms of the

After returning to Philadelphia on 1 January 1931, ''Wyoming'' was placed on reduced commission. Under the terms of the London Naval Treaty

The London Naval Treaty, officially the Treaty for the Limitation and Reduction of Naval Armament, was an agreement between the United Kingdom, Japan, France, Italy, and the United States that was signed on 22 April 1930. Seeking to address is ...

signed the previous year, ''Wyoming'' was to be demilitarized. During the demilitarization process, her anti-torpedo bulges, side armor, and half of her main battery guns were removed. She was back in service by May, and on the 29th, she took on a crew of midshipmen from Annapolis for a training cruise to Europe, which began on 5 June. While en route on 15 June, ''Wyoming'' rescued the disabled submarine and took it under tow to Queenstown, Northern Ireland. While in Europe, she stopped in Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( or .; da, København ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a proper population of around 815.000 in the last quarter of 2022; and some 1.370,000 in the urban area; and the wider Copenhagen metropolitan ar ...

, Denmark, Greenock, Scotland

Greenock (; sco, Greenock; gd, Grianaig, ) is a town and administrative centre in the Inverclyde council area in Scotland, United Kingdom and a former burgh within the historic county of Renfrewshire, located in the west central Lowlands o ...

, Cadiz, Spain, and Gibraltar. The ship was back in Hampton Roads on 13 August; while on the cruise, ''Wyoming'' was reclassified as "AG-17", to reflect her new role as a training ship.

''Wyoming'' spent the next four years conducting training cruises for midshipmen and NROTC cadets to various destinations, including European ports, the Caribbean, and the Gulf of Mexico. On 18 January 1935, she carried the 2nd Battalion, 4th Marine Regiment, from Norfolk to Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico (; abbreviated PR; tnq, Boriken, ''Borinquen''), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico ( es, link=yes, Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, lit=Free Associated State of Puerto Rico), is a Caribbean island and Unincorporated ...

for amphibious assault exercises. On 5 January 1937, the ship left Norfolk and steamed to the Pacific via the Panama Canal. She took part in more amphibious assault exercises and gunnery drills at San Clemente Island

San Clemente Island (Tongva: ''Kinkipar''; Spanish: ''Isla de San Clemente'') is the southernmost of the Channel Islands of California. It is owned and operated by the United States Navy, and is a part of Los Angeles County. It is administered b ...

. On 18 February, during the exercises, a 5-inch shrapnel shell

Shrapnel shells were anti-personnel artillery munitions which carried many individual bullets close to a target area and then ejected them to allow them to continue along the shell's trajectory and strike targets individually. They relied almo ...

exploded as it was being loaded into one of her guns. The blast killed six Marines

Marines, or naval infantry, are typically a military force trained to operate in littoral zones in support of naval operations. Historically, tasks undertaken by marines have included helping maintain discipline and order aboard the ship (refle ...

and wounded another eleven. ''Wyoming'' immediately steamed to San Pedro and transferred the wounded Marines to the hospital ship

A hospital ship is a ship designated for primary function as a floating medical treatment facility or hospital. Most are operated by the military forces (mostly navies) of various countries, as they are intended to be used in or near war zones. ...

.

On 3 March, ''Wyoming'' left Los Angeles, bound for the Atlantic. She reached Norfolk on 23 March, where she served as the temporary flagship for Rear Admiral Wilson Brown, the commander of the Training Squadron, from 15 April to 3 June. On 4 June, she left port to conduct a goodwill cruise to Kiel

Kiel () is the capital and most populous city in the northern Germany, German state of Schleswig-Holstein, with a population of 246,243 (2021).

Kiel lies approximately north of Hamburg. Due to its geographic location in the southeast of the J ...

, Germany, arriving on 21 June. There, she visited ''Admiral Graf Spee''. She left Germany on 29 June, stopping in Torbay, Britain, and Funchal, Madeira

Funchal () is the largest city, the municipal seat and the capital of Portugal's Autonomous Region of Madeira

)

, anthem = ( en, "Anthem of the Autonomous Region of Madeira")

, song_type = Regional anthem

, image_map=EU-Portugal_with_Madei ...

, and arrived in Norfolk on 3 August. ''Wyoming'' resumed her training ship duties for Naval and Merchant Marine Reserve units. She returned to Norfolk Navy Yard for an overhaul that lasted from 16 October to 14 January 1938.

''Wyoming'' performed her typical routine of training cruises in the Atlantic through 1941. The cruises included another European trip in 1938; she took the midshipmen to Le Havre, France, Copenhagen, and Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

. After the outbreak of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

in Europe in September 1939, ''Wyoming'' was assigned to a naval reserve force in the Atlantic, alongside the battleships ''New York'', ''Arkansas'', and and the aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

. ''Wyoming'' became the flagship of Rear Admiral Randall Jacobs, the commander of the Training, Patrol Force on 2 January 1941. In November, ''Wyoming'' became a gunnery training ship. Her first cruise in this new role began on 25 November; she was cruising off Platt's Bank in the Gulf of Maine

The Gulf of Maine is a large gulf of the Atlantic Ocean on the east coast of North America. It is bounded by Cape Cod at the eastern tip of Massachusetts in the southwest and by Cape Sable Island at the southern tip of Nova Scotia in the northeast ...

when she received word of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii, j ...

on 7 December.

World War II

Following the United States' entrance into World War II, ''Wyoming'' performed her normal duties as a gunnery training ship with the Operational Training Command, United States Atlantic Fleet starting in February 1942. She operated primarily in the Chesapeake Bay area, and frequent sightings of the ship steaming around the bay earned her the nickname "Chesapeake Raider". ''Wyoming'' was very busy, training thousands of anti-aircraft gunners on weapons ranging from light .50 caliber (12.7 mm) guns to medium-caliber 5-inch guns for the rapidly expanding American fleet. Early in the war, the Navy briefly considered converting ''Wyoming'' back to her battleship configuration, but decided against the plan.

These duties continued throughout the rest of the war. ''Wyoming'' was modernized at Norfolk Navy Yard from 12 January to 3 April 1944; the reconstruction removed the last of her three 12-inch gun turrets, and replaced them with four twin and two single enclosed mounts for 5-inch/38 caliber guns. New fire control radars were also installed; these modifications allowed ''Wyoming'' to train anti-aircraft gunners with the most modern equipment they would use while in combat with the fleet. She was back in service in the Chesapeake Bay by 10 April. Over the course of the war, ''Wyoming'' trained an estimated 35,000 gunners on seven different types of guns: 5-inch, 3-inch, 1.1-inch, 40-millimeter, 20-millimeter, .50 caliber, and .30 caliber (7.62 mm) weapons. Due to her extensive use as a gunnery training ship, she claimed the distinction of firing more ammunition than any other ship in the fleet during the war.

''Wyoming'' finished her gunnery training duties in the Chesapeake area on 30 June 1945, when she left Norfolk for the New York Navy Yard, for further modifications. Work was completed by 13 July, after which she left for

Following the United States' entrance into World War II, ''Wyoming'' performed her normal duties as a gunnery training ship with the Operational Training Command, United States Atlantic Fleet starting in February 1942. She operated primarily in the Chesapeake Bay area, and frequent sightings of the ship steaming around the bay earned her the nickname "Chesapeake Raider". ''Wyoming'' was very busy, training thousands of anti-aircraft gunners on weapons ranging from light .50 caliber (12.7 mm) guns to medium-caliber 5-inch guns for the rapidly expanding American fleet. Early in the war, the Navy briefly considered converting ''Wyoming'' back to her battleship configuration, but decided against the plan.

These duties continued throughout the rest of the war. ''Wyoming'' was modernized at Norfolk Navy Yard from 12 January to 3 April 1944; the reconstruction removed the last of her three 12-inch gun turrets, and replaced them with four twin and two single enclosed mounts for 5-inch/38 caliber guns. New fire control radars were also installed; these modifications allowed ''Wyoming'' to train anti-aircraft gunners with the most modern equipment they would use while in combat with the fleet. She was back in service in the Chesapeake Bay by 10 April. Over the course of the war, ''Wyoming'' trained an estimated 35,000 gunners on seven different types of guns: 5-inch, 3-inch, 1.1-inch, 40-millimeter, 20-millimeter, .50 caliber, and .30 caliber (7.62 mm) weapons. Due to her extensive use as a gunnery training ship, she claimed the distinction of firing more ammunition than any other ship in the fleet during the war.

''Wyoming'' finished her gunnery training duties in the Chesapeake area on 30 June 1945, when she left Norfolk for the New York Navy Yard, for further modifications. Work was completed by 13 July, after which she left for Casco Bay

Casco Bay is an inlet of the Gulf of Maine on the southern coast of Maine, New England, United States. Its easternmost approach is Cape Small and its westernmost approach is Two Lights in Cape Elizabeth. The city of Portland sits along its south ...

. There, she joined Composite Task Force 69 (CTF 69), under command of Vice Admiral Willis A. Lee. ''Wyoming'' was tasked with developing tactics to more effectively engage the Japanese kamikaze

, officially , were a part of the Japanese Special Attack Units of military aviators who flew suicide attacks for the Empire of Japan against Allied naval vessels in the closing stages of the Pacific campaign of World War II, intending to d ...

suicide aircraft. The gunners conducted experimental gunnery drills with towed sleeves, drone aircraft, and radio-controlled targets. On 31 August, CTF 69 was renamed Operational Development Force, United States Fleet.

''Wyoming'' continued in this unit through the end of the war, and began to be used to test new fire control equipment. In the summer of 1946, then-Ensign

An ensign is the national flag flown on a vessel to indicate nationality. The ensign is the largest flag, generally flown at the stern (rear) of the ship while in port. The naval ensign (also known as war ensign), used on warships, may be diffe ...

Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he previously served as th ...

, the future President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United Stat ...

, came aboard as part of the final crew of the old battleship. On 11 July 1947, ''Wyoming'' put into Norfolk and was decommissioned there on 1 August. Her crew was transferred to the ex-battleship , which was also serving in the gunnery training unit. ''Wyoming'' was stricken from the Naval Vessel Registry

The ''Naval Vessel Register'' (NVR) is the official inventory of ships and service craft in custody of or titled by the United States Navy. It contains information on ships and service craft that make up the official inventory of the Navy from t ...

on 16 September, and she was sold for scrapping on 30 October. She arrived on 5 December in New York, where she was dismantled by Lipsett, Incorporated.

Notes

Footnotes

Citations

References

* * * * * * * * *External links

NavSource Naval History, USS Wyoming (BB-32)

Log of the U.S. Ship ''Wyoming'', 1936, MS 89

an

U.S.S. ''Wyoming Diary'', 1917-1919 (bulk 1918), MS 31

held by Special Collections & Archives, Nimitz Library at the United States Naval Academy {{DEFAULTSORT:Wyoming (BB-32) Wyoming-class battleships Ships built by William Cramp & Sons 1911 ships World War I battleships of the United States World War II battleships of the United States